The Fight-or-Flight Response – Getting away from danger

What is the Fight-or-Flight Response

The fight-or-flight response is an automatic physiological reaction triggered when we perceive a threat or danger. Fight-or-flight is an active defense reaction. The fight-or-flight response occurs immediately, if danger is present. If a predator is detected, the prey animal would immediately start running.

- Flight patterns – Getting away – Running away, seeking cover – The instinct activated is full panic

- Fight patterns – Moving towards the danger – Attacking, fighting, hitting, biting, making snarling sounds – The instinct activated is killer rage

Flight is usually the first response. If I can, I will try to run away. Fleeing is the first response, given that a fight is dangerous for me and I may kill / hurt another person. Fighting becomes an option, if I cannot easily get away.

Flight is usually the first choice.

The Physiology of the Fight-or-Flight Response

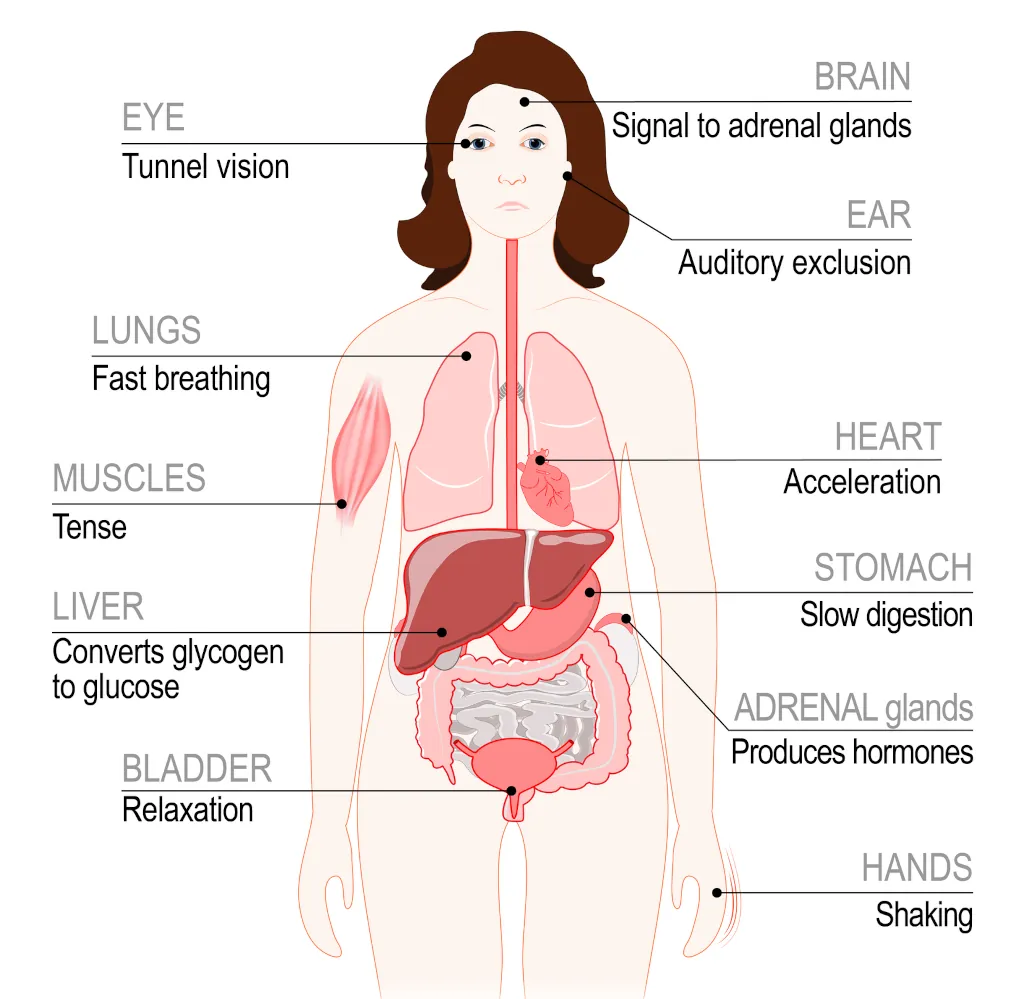

During an active fight-or-flight response, attention narrows to focus on actions necessary for survival. The body releases stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, preparing us to escape from the threat or forcefully confront it. The body goes into full survival action and displays either flight-or-fight – depending on the situation (how close / large is the danger) and depending on available resources (e.g. combat skills, physical strength).

This results in tunnel vision, fast heartbeat, less blood in the bowels and more blood in the muscular system, heart and brain. Breathing gets faster. At the same time routine digestive tasks are put on hold. Furthermore the pain processing ins reduced through neurotransmitters and blocking of nerve signals.

- Muscles are fully mobilized from the amygdala and the limbic system with an instinctive reaction (i.e. not mediated by the conscious brain). Depending on the most promising course of action and available automatic skills the unconscious picks the most effective strategy.

- The nervous system is fully activated from the sympathetic nervous system and through stress hormones. At the same time the parasympathic tone is reduced, which further supports to increase the overall level of activation.

During fight-or-flight the body goes into full sympathetic nervous system activation and muscle activation. Pain processing is reduced.

PTSD Symptoms – Overactive Fight-or-Flight Response

Being stuck in fight-or-flight responses contributes to PTSD symptoms and reinforces the trauma’s emotional and physical impact. The sustained activation of this response system keeps sufferers anxious, agitated, and overactive. This makes it difficult to feel safe and secure in the environment. Other symptoms such as flashbacks, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts may further active the fight-or-flight-response.

In individuals with PTSD, specific symptoms of unprocessed fight-or-flight response may include:

- Avoidance of triggers

- Flight symptoms

- Strong urge to leave the interaction (i.e. flee)

- Being prone to strong nervousness / fear

- Panic attacks

- Fight symptoms

- Verbal or physical aggression

- Having a “short fuse” (i.e. exploding easily into anger)

- Easily going into a killer rage and start fighting

- Moral injury

- Shame, guilt and rumination about the behaviour displayed during fight-or-flight

Avoidance of Triggers

A key symptom of PTSD is avoidance of Triggers, which generally reflects that individuals would like to avoid falling into instinctive reactions. Such instincts generally are uncomfortable – no matter if they comprise fear / panic or aggression rage. The person may therefore avoid situations where instead of little fear, full blown panic is caused or where they could harm themselves or others.

Flight Symptoms

Flight symptoms as part of PTSD can be in a variety of intensities: They may include the urge to leave the situation immediately, but also numbing out and daydreaming, like not being really here. Internally the person may feel that they are prone to go into fear / anxiety in a fast way. Under the condition of an overactive flight-reflex, anxiety can easily rise up to an unbearable level and become panic.

Fight Symptoms

Fight symptoms as part of PTSD can be in a variety of intensities: On the less intense end of the spectrum,, they may range from more subtle forms of verbal aggressiveness and easily being defensive. Stronger forms may include physical violence (e.g. domestic violence or being prone to fistfights).

Other people may notice that the person is easily angry or prone to altercations and arguments. Internally the person may feel that they have “a short fuse” or get angry quickly. The person may be aware that in this state, it may be dangerous to others or himself (i.e. prone to get into very dangerous fights).

Moral Injury

Moral injury is a more subtle form of not fully integrating fight-or-flight. In this case, after the shock experience is over, sufferers remain consciously focused on the acts during the survival through fight-or-flight.

Given that in the shock-situation itself the full focus is on survival above all other considerations, it likely that the person in ensuring survival violated own norms and values. This results in moral injury. E.g., the person may feel guilty for the acts it had to do in order to survive. Fight-responses may have injured other people physically. Flight-responses may have left other people alone in danger. And there is the moral / conscious part of the person, who is not happy about what happened during the shock event.

As a result of trauma flight or fight reactions may remain overly active. In addition, moral injury and rumination about one’s behaviour, feelings of guilt and survivor guilt may contribute to PTSD.

Overcoming PTSD – Completing an incomplete Fight-or-Flight responses

With the help of a therapist, you can fully process the fight-or-flight response using trauma-informed therapy approaches:

- Healing the moral injury – Understanding shock situation and survival responses

- Developing rational understanding that survival responses are different than normal every day behaviours and do not follow “normal” norms and values.

- E.g. If going back to save another person would mean that I will die as well rather than getting out, our survival instincts will overrule compassion and caring for others.

- Emotional acceptance and processing of unprocessed emotions like rage, sadness resulting from the moral injury.

- Developing rational understanding that survival responses are different than normal every day behaviours and do not follow “normal” norms and values.

- Energy Management – Developing containment skills

- Using the muscular system to manage energy levels, with the goal to stay in the range of emotions which one can handle and does not fall into instincts.

- This also includes further processing of emotions like anger (instinct: killer rage) and fear (instinct: panic)

- Somatic exercises for mindful movement can support living with trauma and calming the nervous system

- Reactivation of the flight response – Completion of the flight reflex

- Reactivating the flight response involves harnessing the energy of the body and mind to fully mobilise the stuck reflex energy. The Flight response can be reactivated by physical running into the trauma (e.g. Bodynamic Release Run or Somatic Experiencing running). This should only be done with an experienced trauma therapist.

- Befriending the instinct response – Developing flight & fight as competencies

- Befriending the instinct response means accepting the as part of myself which can ensure my survival rather than suppressing / avoiding them.

- This includes developing a self concept of being somebody who can protect oneself by all means necessary.

- This usually also includes working with the inner critic, the conscious part which is not happy about the instinctive survival behaviour.

- Physical exercise – Cultivating the fight reflex

- Martial arts and competitive sports may be possibilities to cultivate the fight energies and learn to control it. This way the range of conscious activation is extended and the person learns to modulate their responses.

- In addition, High intensity exercise may help discharging excess energy in a relatively safe environment.