Overview – Grounding / Orientation / Deep Breathing

Exercises: (Deep) Breathing

Deep breathing effects through the vagus nerve the level of activation of your nervous system. Deep breathing will lower activation to move towards parasympathetic activation, i.e. to lower your heart rate, lower your blood pressure and lower cortisol levels.

Deeper breathing can be stimulated with the following exercise:

- Trust your natural breathing rhythm

- Allow for a natural breathing rhythm. Do not consciously control the breathing rhythm, as consciously controlled breathing can lead to rather unnatural breathing patterns.

- Pause and feel your natural breathing rhythm

- Observe 3-4 complete breathing cycles, whenever you have opportunity to stop and pause.

- Relief/relaxation can often be felt after a conscious, deep inhalation and exhalation

- Breath deep into your belly

- Take about five minutes three times a day to breathe deeply into your belly..

- Deep breaths involve breathing down into the belly by using your diaphragm and expanding your lung space by lifting the chest cavity from the belly up. Breathing should be lead by the diaphragm. The main focus should be breathing with the diaphragm and lifting the overall chest cavity on the front of the body, i.e. lifting the ribs and not pushing the belly out to breath into the diaphragm.

- Note that during the deep belly breaths the smaller breathing muscles of the upper chest will also be activated. These are small muscles between the ribs (m. intercostales) and the upper respiratory muscles (m. serratus anterior and m. serratus posterior and inferior as well as m. scaleni). For this exercise, these muscles should not be the main focus.

- Other considerations

- Following a controlled regime of breathing is not an ideal way of learning to breathe. Breathing should follow a natural rhythm of breathing following the spontaneous breathing in and breathing out reflexes.

- Learning to breathe deeply can however be aided by a number of specific techniques. There are also guided meditations and smartphone apps such as Insight Timer or Breathe.

How to integrate in daily life:

- A few breaths are enough for deep breathing. You can do this at any time. Pause, take a few deep breaths in and out, focusing on the exhale.

- As mentioned above, you can also use waiting times or time on public transport.

Background & Further Study

The beneficial effects of breathing techniques are well documented. Many studies have found these effects for stress reduction (see e.g. here) and cortisol levels (see e.g. here) documented in scientific studies.

The following exercises (Grounding and Orienting towards Safety) stimulate the relaxation response. The result is that the breathing deepens naturally.

Exercises: Active Grounding – Sense your Feet & Soften your Knees

Grounding provides a deep connection to the earth and to the current reality in general. It takes us away from our thoughts and through our body to the connection with the external reality that we share with other people. It also enables us to assert ourselves, to feel rooted and supported by the ground.

Ground yourself using your entire feet, lower legs, knees and legs.

- While sitting, put your feet flat on the floor. Going back and forth between forefoot and heel: Lift the forefoot and lower the forefoot. And lift the heel and lower the heel. Go for a couple of minutes through several cycles. Be mindful what is happening in your body as you do it.

- By using the muscle on the frontside / outer side of the shin bone (m. tibialis anterior) way, you get a better sense of comparing your imagination / fantasy and the actual outer reality. Similarly you will improve your ability to distinguish intension from action and and your ability to move between abstract and concrete / specific.

- By using the muscles on the calves (m. gastrocnemius and m. soleus) you improve your power behind action and choice and being able to stand on your own and standing-up for yourself while being in contact to others.

- Ground yourself by grabbing into the ground with your toes

- This way you activate the flexors of the toes, which allow us to firmly “grab” the reality and maintain a sense of reality and distinguish realität from fantasy. Being supported by reality, we can move forward in life in line with our needs and follow our curiosity.

- Make your knees flexible

- While standing, bend your knee a little and unlock it. Gently alternate between straightening the knee and softly releasing it until both positions are equally comfortable.

- Then keep your feet on the ground and gently bounce up and down with a flexible knee – activating the locking and unlocking muscles around the knee

- In this way, you can gradually get out of various stuck trauma reactions, which can be stored in particular in the knee’s locking and unlocking muscles (vastus medialis and popliteus muscles):

- Locked knees: You may be coming out of locked freeze reactions (indicated by a flaccid popliteus muscle and hypertonic vastus medialis muscle).

- Soft knees / “folding”: You may also be coming out of a tendency to collapse the legs (indicated by a hypertonic popliteus muscle and flaccid vastus medialis muscle).

- You also get more flexible in connecting to the reality and less stuck / frozen, so you will find it easier to change course and take action.

How to integrate in daily life:

- From time to time take a mini-break at work do the exercises with your feet and toes, maybe also get up from your desk and ensure your knees are flexible.

- Use waiting times, in which you stand for a few moments (public transport, tills, lifts etc.) to ensure that your knees are unlocked and flexible. Then take a moment to sense and grab with your toes.

- When walking somewhere, take a few minutes more and stop from time to time for a minute or two to do the exercise.

- You can combine this exercise with the Orienting for Safety-Exercise.

Background & Further Study

It is known from practical experience with grounding exercises that grounding often triggers a rapid parasympathetic relaxation response. Therefore, using the exercises mentioned above can also be useful for stress regulation and regulation of cortisol levels. While a direct connection between grounding muscle activation and cortisol levels has not been studied (to my knowledge), the effects of mindfulness exercises in general on relaxation and cortisol regulation are well researched and documented.

The psychological effect of grounding and its link to the muscular system has been researched and documented by Lisbeth Marcher. Grounding using the leg and foot muscles is one of the fundamental Ego Functions of the Bodynamic®-System. The above exercises are inspired by Bodynamic. Particularly the comments above regarding the psychological functions of the toe flexors, m. tibialis, m. soleus and m. popliteus are based on L. Marcher’s work.

Exercises: Orienting towards Safety

Orientation – Looking while Moving your Neck

Orientation plays an important role in reviewing our safety and developing optimal strategies for action. Orientation is the antagonist to our threat detection system. This warning system pays attention to dangers and possible threats and initiates physiological preparatory measures. If not oriented enough, the stress of potential threats can spread unchecked, leading to elevated levels of stress hormones over time. Orientation distinguishes real dangers from possible dangers. If there is no danger, we can feel safe. This allows our body to calm down and go back to normal.

Orienting in reality

Grounding (into the current reality) and orienting to fully understand the current reality go hand in hand:

By orienting we find our way in the current reality, including the social reality of other people and our relationships towards them. Most the time, through thorough orientation, we will notice the (relative) safety in the here and now. We orient towards the actual reality / possible safety and away from potential and (consciously or unconsciously) imagined possible threats. In this way, we can deal effectively with the actual issues at hand.

Orienting involves both orienting in space (“Are there any threats around me right now?”) and in time (“As the situation evolves, will there be any threats in the near future?”). Orienting in time includes orienting the focus towards the present and the near term future (which is actionable) and away from threats in the past or an imagined future which is not directly connected to the current reality.

Orienting and Stress Response

The orienting reflex is a vital natural part of our stress response: If a potential threat appears we stop and orient to see if there is actually a threat. If there is no threat, we realise that we are safe and we can calm down. This insight also brings us from an activated instinct system (brainstem / limbic system) back into our pre-frontal cortex, which is necessary to perform complex tasks. Orienting in most situation in normal life therefore increases a feeling of safety by becoming aware of the safety and becoming more capable in dealing with the situation at hand.

For our ancestors orienting was a concrete physical activity. Subsequently it is important to orient also in in a practical way towards the tasks and people in your daily life.

Exercise: Orient with movement and the visual sense

The exercise below activates the muscles involved in orienting-for-safety. Through moving your neck and eyes to orient, you basically complete the orienting response and can return to a feeling of safety. This exercise helps to to move beyond the initial freeze (which affects the knees as well as the neck) when reacting towards a threat.

- Move your neck for 180 degree vision. While sitting or standing follow your nose with your glance and turn your head slowly in both directions by moving your neck. Gently turn your head / the direction of your vision all the way to the left and to the right, without stretching or causing pain. Do this for 3 minutes.

- While you do the movement, see what is around you, who is there with you?

- Notice at least 5 items / people around you.

- Connect to people and even items in the space around you by looking at them.

- Realize (with conscious though) what create safety for you.

- Notice, that the situation is safe in this room and with the people present.

- Move neck and eyes for 360+ degree vision. Increase the first exercise by turning your head all the way to each side (without straining your neck!). When in the maximum position, slowly turn your eyes maximum in the same direction. Notice that you have more than 360 degrees in vision this way.

- Realise that you are safe in this room and with the people present (Details see above).

Exercise: Orientation with the visual sense / through visual impressions

Safety can also be established through actual sensory impressions – in a natural way by scanning the environment (and can be combined with the exercise above).

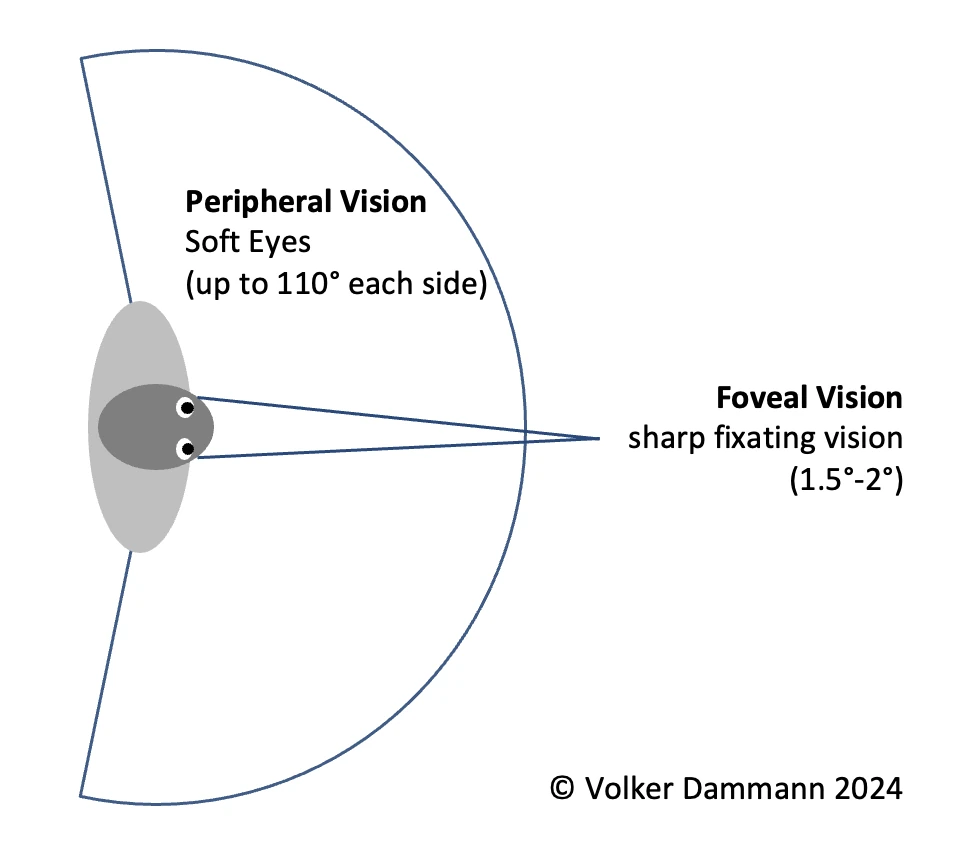

Safety is created in the here and now through connection with what can actually be seen visually. That is, as I swing my glance from left left right, I let in actual sensory stimuli. This is best done by – on the one hand – briefly focusing and connecting with what can be seen and – on the other hand – by taking a panoramic view.

In contrast, a feeling of uncertainty can arise from being in one’s head and from conscious or unconscious imaginations. This means that one sees neither the real forest nor the real individual trees, but is instead seeing internally imagined images – memories of the past or an imagined future. The eyes are often defocused. Or the eyes look in the direction of the internal images, which are often stored spatially.

In the following exercise we use both Visual Focusing and Panoramic Viewing – alternately or in any order:

- Short term focusing – Foveal vision (“Seeing the individual trees”):

See an object or person and then move on to the next. Verbally name what you see (“sidewalk….balcony…tree…flowerbed…fence…dog”). If you only stay briefly with the individual items, until you notice some familiarity with the items as well as the security from knowing the name. Then move on to the next one. Notice how you arrive through the individual things/people in the here and now and get an overview. - Panoramic view – Peripheral vision (“Perceiving the forest”):

Focus on the big picture. Look at the panorama. Notice how you can also see something at the edge of your field of vision without looking at it. Movements are particularly noticeable at the edge of the field of vision. Name the big picture. Notice how you get an overview and security by looking at the panorama.

Exercises: Orienting through other senses

Orienting goes beyond just the visual sense. it can be very powerful to involve other senses. This creates safety beyond the visual system, which can be very powerful to deepen the experience of safety.

With proper awareness, do the following exercise as part of a standalone exercise. – Please stop. Stop any activity/walking motion you are doing. Do not do the exercises while driving.

- Hearing: Notice what you can hear.

- Do you know where those sounds come from and what they mean?

- Which sounds denote safety? Which denote possible danger?

- Smelling: Notice what you can smell.

- Smelling can convey all sorts of danger information (think of smoke for example)

- Which smells denote safety? Which denote possible danger?

- Sensing: Notice what you can sense

- Is there anything to sense in the enviroment (e.g. vibration of the ground)

- What else to you sense?

- Internal sensing

- Notice your own body and how it feels.

- Is there any sense of foreboding?

- How is your body safe right now?

How to integrate in daily life:

- Practice: Do the exercise and activate your orienting muscles regularly:

- When going about your daily business, plan 5 minutes more. When walking somewhere stop for a few moments and look around. Make your environment safe for you by fully taking it in.

- Application: Activate your muscles ahead of decisions or in situations where you feel overwhelmed.

- Orienting before decisions

Before making decisions, take a moment to stop, activate the orienting muscles combined with the visual sense and the other senses (hearing, smelling, body sensing) and notice that you are safe.

- Orient socially and towards tasks

Orient in your professional role, towards your task at hand, in your Email Inbox etc. and also with regard to the people you interact with socially.- Orient practically by navigating structure / plans

Practically orient yourself in a complex situation by giving it structure. Considering using flow charts, organigramms or overviews of numbers to understand the situation. Use planning tools to orient towards the complex tasks (by creating / reviewing project plans, to-do lists, Gantt-chats, calendars etc.)

Background & Further Study

The link between situational stress focus and elevated cortisol levels is documented scientifically. Similarly the correlation between orienting towards stressors and elevated cortisol levels have been documented scientifically – conversely orienting towards safety is leading towards relaxation and lowering of the stress response.

Further reading / Exercises: The effect of orienting and its relationship to the muscular system has been researched and documented by Lisbeth Marcher. Orientation is one of the basic ego functions of the Bodynamic System. The throat and neck muscles play a particularly important role in orientation. The Bodynamic®-System teaches further muscle activation exercises including exercises to orient using the neck muscles.