The Fawn Response – Please and Appease – Background

The please and appease strategy is an adaptive survival style aimed at pacifying the perpetrator and in this way making the situation more safe for the trauma victim. It applies in situation where the victim is trapped with the perpetrator and flight-or-fight does will likely not succeed.

This strategy usually develops in early childhood as the child tries to make the relationship to his parents / caretakers more safe by going the extra mile to please his caretakers. It can also develop during prolonged trauma when victims try to appease the perpetrator and in this way maintain a minimum of personal agency. An example would be the so called Stockholm-syndrom.

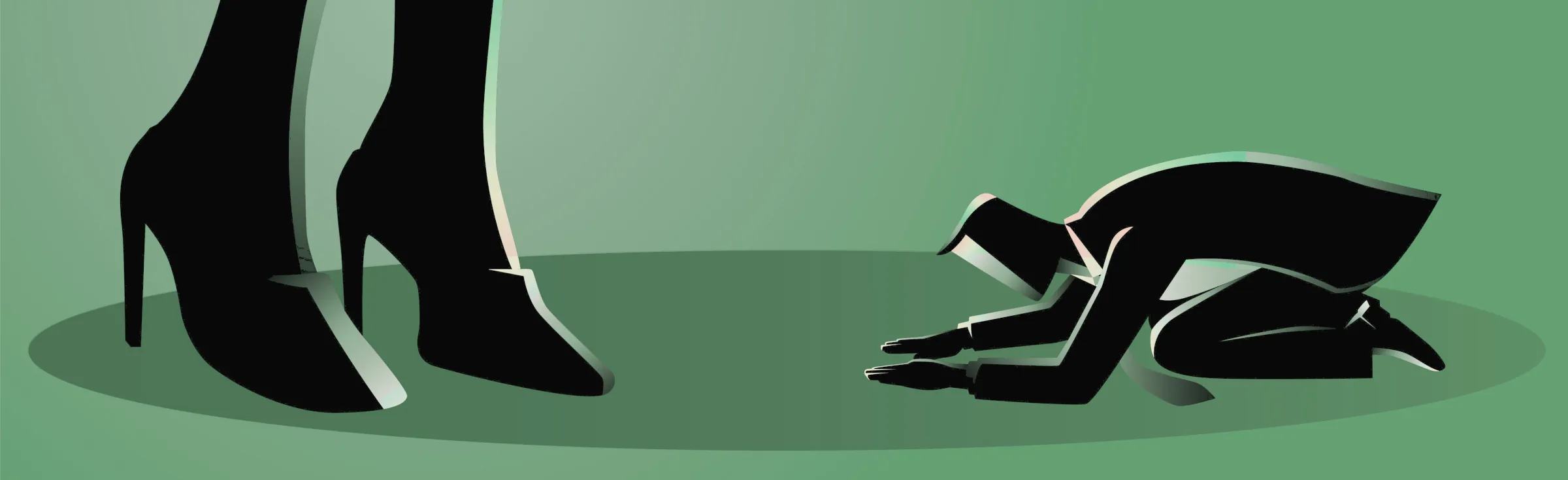

In the acute shock situation, the fawning response may include submissive behaviors, which aim to prevent or interrupt aggressive actions by the perpetrator. These behaviours are varied and differentiated and include a mixture of taking action and resigning-one’s individually:

- On one end of the spectrum we find behaviours like “automatic obedience and helpless compliance”, these can be rather mechanical behaviours. At the same time the body-language may display “crouching, avoiding eye contact, and generally appearing physically smaller and therefore non-threatening” (cf. P. Ogden et al, 2006).

- At the other end of the spectrum, we may find sophisticated interactions that appear (only to observers who don’t understand the context!) to look like voluntary social engagement and may require a mix of automatic skills and deft negotiation tactics.

These more sophisticated tactics boil down to give up its own impulses and emotions to a large extend. Interactions are not on eye level. All of these behaviours have the function to make the unsafe relationship to the perpetrator (or more generalized other people) somewhat more safe and prevent negative outcomes.

It can be hypothetized that the underlying nervous system of the victim is highly activated (sympathetic response) but at the same time there are strong elements of giving up (parasympathetic, dorsal vagal response). It can also be observed that the muscle tonus is also given up to a significant degree.

Symptoms of PTSD and Developmental Trauma

The Fawn Response as a PTSD or developmental trauma symptom is characterised by an overwhelming desire to please others and prioritise their needs above one’s own. Those who exhibit this response may find themselves in their daily life excessively accommodating, avoiding conflict at all costs, and constantly seeking validation and approval from others.

Internally, people may experience feelings of chronic guilt and shame, a diminished sense of self-worth, and difficulties in authentic self-expression. They may lack access to anger. They may habitually sacrifice their own needs, desires, and values to maintain relationships or avoid confrontation, ultimately compromising their well-being in the process.

Individuals often struggle with asserting their own preferences, and maintaining a healthy sense of self. The person may be unable to defend their boundaries, take on too many burdens and end up in co-dependent relationships.

Externally, sufferers may display to others overly placating, appeasing behaviours, despite being in otherwise safe relationship contexts. Overall they behave like a Placator type (Virginia Satir-Categories), take less space with their body and take less space in conversations.

Dominant (and abusive) individuals tend to seek out victims with appeasement tendencies. On the other hand, individuals, who seek a relationship on eye level may be annoyed by the lack of own initiative, lack of spine and overly comforting behaviour. The person self may suffer from frequent violations of boundaries and repetition of earlier violations.

Reprocessing PTSD and Developmental Trauma – Self Assertion instead of Please and Appease

Addressing the Fawn Response in Therapy involves creating a safe space for individuals to explore their patterns and understand the reasons for adopting this coping mechanism.

Therapy often begins with emotions and behaviors in daily life that the person would like to change and be more confident about. This gradually builds safety and allows for recognition of survival strategies. This lays the groundwork for renegotiating underlying shock trauma. Alternatively – in the case of developmental trauma – it is about re-evaluating the quality of the parental relationship and finding a new relationship with the adaptive style of survival that was necessary as a child in that environment.

Trauma-focused therapeutic techniques such as Somatic Experiencing® can aid in processing the original trauma and build self-compassion. Approaches like Bodynamic® can help with establishing healthy boundaries, and fostering assertiveness skills and positioning towards others.

- Strengthening the Body Ego and Individual Ego to strengthen the core of personality

- Developing the Body Ego: Work to strengthen Centering, Grounding, Boundaries – Work with Bodynamic Exercises to strengthen these Ego Functions from the muscular system.

- Developing the Individual Ego: Work with building an inner sense of needs and impulses. Work with decision making and positioning these decisions towards others.

- Working through emotions in daily life

- Working through shame and guilt.

- Rediscovering healthy anger.

- Reprocessing original shock trauma

- Make space for and reintegrate suppressed / dissociated emotional distress, i.e. look to integrate anger, fear etc.

- Acknowledging and integrating the survival strategies.

- Reprocessing the original Developmental Trauma

- Reevaluating the relationship to the parents – acknowledging what needs were not fulfilled and what type of abuse was suffered.

- Make space for and reintegrate with suppressed / dissociated emotional distress, i.e. look to integrate anger, fear etc. – Also look at shame and compensatory pride and make space for healthy (red) shame.

- Reactivating relevant muscles to rebalance need, impulses and own decisions

- Rebuilding the relationship to abandoned parts of the personality

- Work with parts who have withdrawn to cope with the shock or develomental trauma

- This usually also includes working with the Inner Critic, the part which thinks one is not good enough unless one is keeping others happy. There may be further parts, which are not happy with giving up one’s own personality.

- Establish self care in the here and now.

- Building internal strength to build healthy external relationships

- Activating the ego functions of assertiveness, positioning, social balance and interpersonal skills to reposition yourself in life today.

- Bodynamic exercises to strengthen these ego functions through the muscles.

- Practical conflict resolution in daily life

- Learn to manage conflicts and relationship hick-ups in every day life.

- Develop practical self assertion and conflict resolutions skills.

- Post-traumatic growth: Re-Evaluate Self Concept and Identity

- Develop a self concept of being somebody who can will take care of his own needs / impulses before taking care of other

Sources / further Reading

Ogden, P., Pain, C., & Fisher, J. (2006). A sensorimotor approach to the treatment of trauma and dissociation. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2005.10.012

(available at http://www.franweiss.com/pdfs/sensorimotor_ogden_etal_2006.pdf)

Walker, P. Codependency, Trauma and the Fawn Response;

https://www.pete-walker.com/pdf/CodependencyTraumaFawnResponse.pdf